A Short History of The Town of Abington

Including Rockland and Whitman, Massachusetts

Long before Abington, Massachusetts became a town, the Algonquins migrated eastward from the Great Lakes region and assimilated with the local tribes. As they settled in, they brought with them the tradition of applying descriptive names to particular localities. Hence when they came upon a meadow with tall grass waving in the wind, they called the place Manamooskeagin, meaning “great green place of shaking grass.” The Abington town seal incorporates its Algonquian name.

|

These semi-agrarian tribes had regular campsites at Wessagusset (the salt-water fishing place) — what is now North Weymouth — in the winter, and at Robbins Pond in East Bridgewater in the summer, where they planted corn, beans, and squash. The path they used to travel between the two encampments was called “Satucket,” a shortened form of the Algonquin word “Massaquatuckquett,” which means “great pouring-forth stream place” — referring to the where the river flowed out of the pond.

Old Abington was located in what was a buffer strip between the Massachuset and the Wampanoag tribes, both of whom claimed the territory. This controversy led to continual border skirmishes in the area between the two tribes. It is probably for this reason that there were no Native American settlements here. When Plymouth Colony began awarding land grants to individuals for public service to the colony, the lots were located in this area—on land purchased from the two tribes. These land grants were located along the Satucket Path, which over time evolved into what is now Washington and Adams streets in Abington. None of the original land grant recipients actually settled in Abington. It was purchasers of the titles to the land that moved into the area. |

The first settler of record was Andrew Ford, originally from Weymouth, who moved to Abington in the 1660s. His first house was located on the knoll above the “Stepping Over Place” on the Schumatuscacant River (now at the fork in the road of Adams & Washington streets). The Fords seem to have been a typical Colonial frontier family. They maintained ties with their family in Weymouth, but they were more-or-less self sustaining in their daily lives.

As far as the indigenous peoples were concerned, the Ford family pretty much kept to themselves; there does not appear to have been any attempts to associate with them. Other families soon followed, with names such as Dyer, Gurney, Harden, Hersey, Nash, Poole, Reed, Tirrell, and Whitmarsh.

A petition for an act of incorporation was first presented to the General Court in 1706, which was turned down. It was followed by an order that said:

|

“The proprietors, purchasers and inhabitants, to take care to make a subscription of what they were capable and willing to pay annually for the support of an able, learned, and orthodox minister...”

|

Five years later, Rev. Samuel Brown (1687–1749), a native of Newbury, was engaged to serve as the town’s first minister. Thus the last requirement for this settlement to become an incorporated town was finally met. In an autobiographical document titled, A Memoranda of The Remarkables of My Life, Rev. Brown wrote,

|

“I came to Abington, with a unanimous call from ye people there, in order to settle on the 8th of December Anno 1711... I was ordained Pastor of the Church of Christ in Abington Nov 17th 1714.”

|

With an “able, learned, and orthodox minister” to attend to the spiritual needs of the inhabitants, the petition to create a separate town out of a section of east Bridgewater and adjoining lands was approved. The official grant of township established June 10, 1712 as the date that Abington was incorporated as its own town. The town was so named by Gov. Joseph Dudley (1647–1720) to honor Anne Venables Bertie, Countess of Abingdon, England, who had helped him secure the position of royal governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

The first sawmill was in operation ca. 1700 and several others were established soon after. These sawmills provided lumber for building, and consequently promoted settlement of the area. By the time the town was incorporated in 1712, there were about 20 families that lived there.

As with any community, Abington needed a meetinghouse; the first one was built by Jacob Nash in 1710. A one-room schoolhouse was built in 1732 next to the meetinghouse. It was the only school in town for 23 years. In 1755, the town was divided into five school districts and a schoolhouse was built in each district.

A unique natural resource found in Abington was a clay pit located behind the first meetinghouse. The high quality of the clay attracted John Henry Benner, a master potter, to move to Abington ca. 1760. Benner was a German craftsman who had worked at the Glassworks in Germantown (now Quincy). He lived and worked in Abington until the 1790s. Bennerware is recognized as one of the finest examples of colonial pottery.

Several tanneries were established in the area; the first one in present-day Whitman ca. 1710. The availability of leather led to shoemaking as a popular cottage industry involving the majority of the families. Old Abington soon became a one-industry town: shoe manufacture. For the rest of the 18th century, shoes were made in “ten-footer” shops by hand.

Abington’s history is very closely tied to the shoemaking industry. In addition to the natural increase in the families already in residence, young people from other towns moved in because of the shoemaking jobs that were available. They settled here and started their own families. By 1822, population growth required enlargement of the school system into eight districts; and by 1830, there were eleven districts.

The 1850 census records counted 36 boot and/or shoe manufacturers in town. A number of these were still the cottage industry of shoemakers in independent shops. But some were partnerships forming relatively large firms. Over the following decade, the small shops dropped out of business or were absorbed into the larger firms and the business of shoemaking became concentrated in large factories.

|

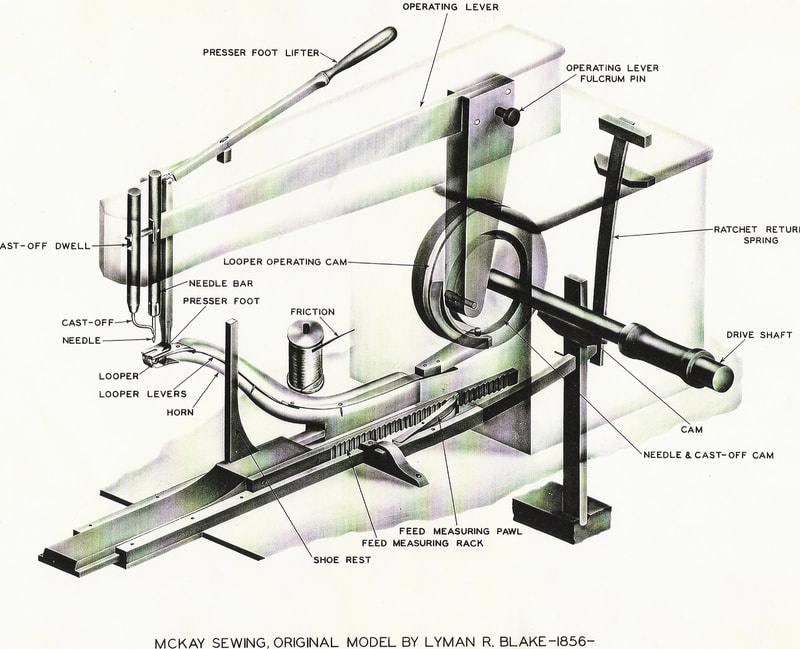

In 1858, Lyman R. Blake (1835–1883), an Abington shoemaker, patented the first machine capable of sewing the soles of shoes to the uppers with satisfactory results. He sold the rights to his patent to Gordon McKay (1821–1903) of McKay Shoe Machinery Co., who patented an improved version in 1862 and promoted their use by the growing shoe industry. These machines were instrumental in transforming shoe making from the backyard “ten-footer” shops to large factories.

During the Civil War, the Union army was in desperate need of footwear — quickly. Because of the timely installation of the McKay machine by the shoe companies, Old Abington was in a unique position to fill that need. Seth Bryant of East Bridgewater, won the contract to provide shoes for the entire Union force. He sub-contracted half the job to manufacturers located in Old Abington, including Arnold, Commonwealth, Crossett, Hurley, Regal, Turner, and Wright. |

Prior to the Civil War, Island Grove Park was the site for many abolitionist meetings. These spirited meetings undoubtedly contributed to Abington’s active involvement in the anti-slavery movement, and consequently, the Civil War. After the Old Colony railroad was put through in 1845, this idyllic spot became easily accessible and thousands would come to the rallies.

In addition to bringing people to Abington, the railroad service also gave Abington, Rockland and Whitman residents access to other places, especially Boston—allowing them to work in the big city while continuing to live in their own home towns. Thus the commuting lifestyle came about and began the transformation of Abington from an industrial town into a bedroom community.

By the time the Civil War ended, the eastern and southern Abington communities had evolved into their own “villages.” The town had also grown too large to maintain its simple town structure—economically and politically, and several community leaders became proponents of dividing the town.

In 1871, the town voted to build a school in each section of the community. The school built at Center Abington, on Dunbar Street, far exceeded the budget; the town refused to pay the bill and the builder sued. East Abington and South Abington, who managed to build their schools within the budget, became very disgruntled about the whole thing and used this opportunity to create a cause around which they built their campaign for secession. The debate continued for three years and in 1874, East Abington withdrew to become the Town of Rockland. In 1875, South Abington became a separate community, and in 1886 adopted the name of Whitman.

|

Towards the end of the 19th century, Herbert H. Buffum, originally from Hanover, Mass., started a shoe machinery factory in Abington. His primary interest, however, were engines and H. H. Buffum Co. was soon manufacturing motor cars and boat motors. Buffum continued to produce automobiles in Abington until ca. 1910.

This era saw the transition from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles as the means of private transportation. By 1915, all of the streets and roads in town were paved—though still with gravel or crushed stone. However, better surfacing with blacktop was not far behind, demanded by the fast-increasing automobile traffic. |

|

The Great Depression of the 1930s marked the slow decline of large scale shoe manufacture in Abington, Rockland, and Whitman and the last remaining shoe company was dissolved during the 1980s. The resiliency of the people are reflected in the continuing development of the town. When one source of income dwindled or disappeared, they turned to another or made adjustments and adapted their businesses to keep up with the times.

Today, many of Abington, Rockland, and Whitman's residents now either commute to work elsewhere or are involved in the service industry that support the local lifestyle. In any case, with the disappearance of heavy industry in the area, Abington completed its evolution into a bedroom community. |

The Dyer Family

The Dyer family was of English origin; the name was probably given to designate someone by his occupation. The Dyers that this library memorializes are descendants of William Dyer, one of the first settlers of Sheepscot, Maine in the early 1600s.

William Dyer built his cabin on Dyer’s Neck at the mouth of the Dyer River where it joins the Kennebec River. There he raised his family until the beginning of King Philip’s War (1676–1689), when he was killed by Indians.

As the massacre of the settlers continued, the survivors fled to other settlements. William’s two sons, Christopher and John, moved to the Braintree area with their families. After a few years, the Indian disturbance having ceased, they returned to Sheepscot and prospered for a few more years. However, towards the end of the war (1688–1689), hostilities once again broke out in that settlement and Christopher Dyer (ca. 1640–1689) was one of the casualties.

Meanwhile, Christopher’s son, William Dyer (ca. 1663–1750), remained in Braintree when his father and the rest of the family returned to Maine. He married Joanna Chard of Weymouth, and built a cabin at Little Comfort ca. 1699. Little Comfort was located along the Satucket Path in the part of Bridgewater that was later incorporated into the Town of Abington and eventually became the Town of Whitman.

In 1701, William and Joanna’s son, Christopher, was born. An early town map states that he was the first white child born in Little Comfort, but this cannot be substantiated since there were several families who settled in the area many years before his birth.

Christopher Dyer (1701–1786) married Hannah Nash in 1725 and they had seven children: Mary, Hannah, Christopher Jr., Sarah, Jacob, Betty, and James.

Christopher Dyer (1701–1786) married Hannah Nash in 1725 and they had seven children: Mary, Hannah, Christopher Jr., Sarah, Jacob, Betty, and James.

A family legend has it that once while Sarah was milking a cow, a thunder cloud came up and a flash of lightning hit the cow, killing it instantly, and knocked out the bottom of her milk pail – without doing her the slightest injury.

Christopher’s youngest child, James Dyer (1743–1828), married Martha Harden in 1770 and they had two daughters, Anne and Susanna, and a son, James Jr.

Christopher’s youngest child, James Dyer (1743–1828), married Martha Harden in 1770 and they had two daughters, Anne and Susanna, and a son, James Jr.

Capt. James Dyer, Jr. (1782–1863) was active in the War of 1812 where as a lieutenant, he led a company of artillerymen on a march to The Gurnet in Plymouth Harbor. James Dyer, Jr. married Anna (Nancy) [Bicknell] Dunham in 1809; it was his first marriage and her second—she was widowed in 1805 when her first husband, Henry Dunham, died at sea. James Jr. and Anna had two sons, Samuel B. and James, and two daughters, Nancy and Maria. After Anna’s death in 1853, James Jr. remarried. He married Polly [Shaw] Bicknell in 1855; it was the second marriage for both.

Samuel B. Dyer (1809–1894) married Abby H. Jones in 1833. Tragically, she died that same year at 19 years of age and Samuel never remarried.

A few years after his wife’s death, Samuel moved to France — earning him the nickname “Paris Sam” to differentiate him from his first cousins who shared the same first name — and remained there until just before the outbreak of the Civil War in America. Although he never became involved in local politics, Samuel Dyer was very interested in and quietly supported numerous community-centered efforts including Abington’s public library and the volunteer fire department.

|

Samuel’s brother, James B. Dyer (1814–1876) married Lucy Hersey in 1835, and had eight children: Abby, Lucy, Henry, Susan, Samuel, Mehitable, Amelia, and Marietta. The family lived with Samuel in his mansion. His niece, Lucy, distinguished herself by being a member of Simmons College’s first graduating class, earning a Bachelor’s degree in 1906.

Marietta Dyer (1853–1918), Samuel's favorite niece, lived in her uncle's mansion her entire life. As she grew up, she took on the role of hostess of the house; she was its last occupant. She inherited the mansion and her uncle's fortune, out of which she gave the Town of Abington a new public library. Marietta also established the Dyer Memorial Library. The Dyer's mission focuses on histories by and about people connected to the area known as "Old Abington," that today comprise the towns of Abington, Rockland and Whitman, Massachusetts, and performs the following functions: collect, select, deaccess, catalog, preserve, retrieve, interpret, and educate the community and the world about the area's history and culture. |